Slow the hype so Hunter, latest high school track phenom, has time to grow

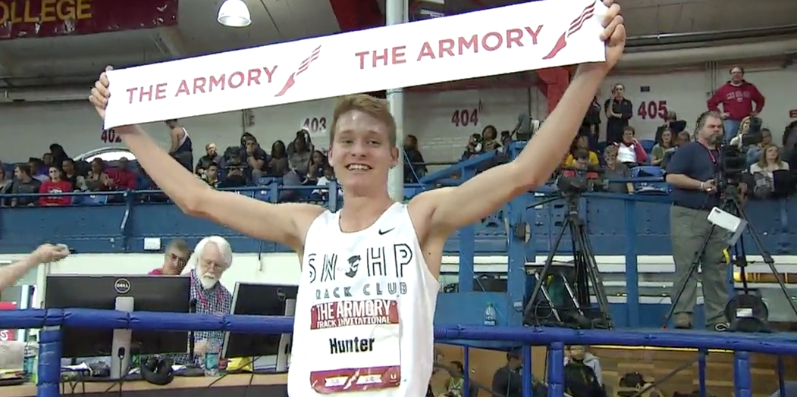

/Drew Hunter after his sub-4 mile Feb. 6 (Image from USATF TV)

In a very small corner of U.S. sports fandom, the biggest story last weekend was not the Super Bowl.

It was the performance of a high school runner named Drew Hunter in a mile race Saturday afternoon at the Armory in New York. Hunter clocked 3 minutes, 58.25 seconds, breaking Alan Webb’s 15-year-old U.S. high school indoor mile record by 1.41 seconds.

The sport-dedicated web sites that do an excellent job of covering track and field were all over Hunter’s achievement -- especially letsrun.com and flotrack.org, which treated it like The Second Coming, which it sort of is for the converted to whom they are preaching.

Not so much the general interest media.

The New York Times published one long sentence about what Hunter had done at a local event. An online search showed The Los Angeles Times and Chicago Tribune had nary a word. The Washington Post, Hunter’s hometown paper, gave him the local hero treatment, putting the story on its Sunday print sports front (although using a brief AP story online.)

All that speaks to how irrelevant track and field has become to the general sports-loving public in this country, even in this Olympic year.

But it may be good for Hunter that his youthful brilliance – he had broken the high school indoor 3,000-meter record a week earlier - has an “if-a-tree-falls-in-the-forest” feel.

That may allow Hunter, 18, to escape any widespread hype or expectations as he develops into a mature runner.

When Webb set his mile record in January 2001, becoming the first high schooler to break four minutes indoors, the New York Times gave it a 673-word story. Three months later, the Philadelphia Inquirer had a 1,500-word story on Webb.

Alan Webb (red jersey) in the mile at the 2011 Drake Relays, where he finished fourth in the mile in 3 minutes, 58. 77 seconds

When he broke Jim Ryun’s 46-year-old outdoor high school mile record in late May of that year at Eugene, Oregon, Webb briefly became a national sports celebrity.

The substantially greater coverage of what Webb had done owed to several factors:

*Ryun’s lasting fame.

*Webb being the first high schooler to break the magical 4-minute barrier indoors.

* The higher – but not high – profile track and field had in the United States before the doping cases that would bring down U.S. Olympic and world champions like Marion Jones, Justin Gatlin and Tyson Gay, as well as many other stars in the sport.

Jones, the defrocked triple Olympic gold medalist who made the cover of Vogue, likely is the only one of those three U.S. sprint champions whose name would ring any bells all over this land – then or now.

Go to any professional team sports event in the United States, ask fans there to name a track and field star, and chances are that the few who can answer will pick Jamaica’s Usain Bolt.

Of course, Hunter may attract a little more attention when he runs the Invitational Mile Saturday, Feb. 20, at the Armory in the Millrose Games, described accurately on its web site as “The World’s Longest Running and Most Prestigious Indoor Track & Field Competition.”

He will be the only high schooler in a Millrose invitational “B” race added for this meet. Once again, that will allow him to be pulled along by collegians and post-collegians like those who essentially became rabbits for Hunter as he outran Webb’s record while finishing seventh. (Click here to watch the race.)

It makes good sense that Team Hunter resisted the lure of having him run the Millrose’s celebrated Wanamaker Mile, where the pace could drive the winning time under 3:50, according to meet director Ray Flynn. He said the Invitational Mile is expected to have a winner around 3:55-3:56.

Webb needed to do something spectacular in almost every race from the minute he broke Ryun’s record if he were to keep commanding general attention, a task not only onerous but impossible. Every time Webb fell short, his stature diminished, even in the track and field world.

Until beset by injuries, which led to his retirement in 2014, Webb had a career full of fast times and minor achievements in major competitions.

Webb owns the U.S. outdoor record for the mile, 3:46.91, set in 2007, the year he also ran his fastest metric mile (1,500 meters). But a year later, he failed to make Olympic team. Four years earlier, in his lone Olympic appearance, he did not qualify for the final. He finished eighth and ninth in his two world championships.

The hype for high school runners like Webb and Hunter is no different than the attention paid to football and basketball college recruits, except there are so many athletes getting premature star treatment in those sports there is not as much focus on each one.

Another difference is there are quantifiable comparisons in track and field.

*Fourteen other runners, including 10 from the U.S., have run faster indoors than Hunter’s mile time this winter. (And he wasn’t even the fastest teen in the race; Aussie Morgan McDonald, 19, ran 3:57.83.)

*Twenty-three other runners, including 15 from the United States, ran faster last season. And many of the world’s best milers eschew the indoor season.

Does that mean Hunter’s time wasn’t impressive? Certainly not. But keeping it in perspective is important.

Well-known Italian coach Renato Canova made that point in a post to the letsrun.com message board thread about the struggles of the previous U.S. prep phenom, Mary Cain. She has gone backwards since turning pro after her breathlessly glorified, record-shattering season, 2013, when she was barely 17.

(Full disclosure: I was among those feeding the Cain hype machine.)

Cain’s ninth-place time in a 1,500 last week in Germany, 4:20.73, has been bettered by 50 other women this winter. It increased the volume of (premature) talk she is washed up before her 20th birthday.

“It's not a problem of form, or of training,” Canova wrote. “It's a problem of mental pressure, that in your country is the main enemy for a right and progressive development of your best talents.

“Since the most part of people following athletics are young students, without any knowledge of the athletic history, there is the trend to give to the best young talents responsibilities they are not yet able to sustain.”

Without such pressure, Matthew Centrowitz has become the most globally decorated homegrown U.S. miler since Ryun.

Centrowitz was an outstanding (4:03) but not record-breaking high school miler. He went on to run for Oregon for three years (following a redshirt first season), winning an NCAA title in the metric mile (after failing to make the final in his first try and getting third the next year.) He has gone on to win silver and bronze medals at the world championships and finish 4th at the 2012 Olympics.

Last season, at 25, he ran career bests in the 800 and 1,500, becoming the third fastest U.S. runner ever at 1,500 – behind Bernard Lagat and Sydney Maree, both of whom grew up (through high school) in Africa. Centrowitz is the 2016 indoor world leader in the mile. (Since I posted this, Nick Willis of New Zealand took the world top spot; he and Centrowitz are scheduled to meet in the Wanamaker Mile.)

Hunter plans to go to Oregon. No matter how long his stay lasts, one can only hope the times of his running life are allowed to come slowly.