An old debate about the young in figure skating heats up again: is it time to raise the minimum age for seniors?

/Alina Zagitova, 15, became the second youngest Olympic women's singles champion.

Is it time to raise the age minimum for singles figure skaters in senior international competition?

Rafael Arutunian thinks so. The coach of the only two U.S. skaters to win senior World Championship medals since 2009 brought up the idea unprompted during our lengthy recent conversation at his training base south of Los Angeles.

For a number of reasons, including health, career longevity and competitive equity, Arutunian favors a minimum age of 18 for senior men and women rather than the current 15.

“Everyone now talks about jumping too much and people starting to damage themselves,” Arutunian said. “How do you want to stop that? In my mind, there is only one way: not allow them to compete (at seniors) until 18.

“If I am 12 years old, and I know real money is after 18, do you think I will do too many quads, or I will do just enough quads to win and save my body for later?”

Several other coaches and skaters contacted by phone, email or text message, including Alexei Mishin of Russia, Brian Orser of Canada and Tom Zakrajsek of the U.S., agreed with Arutunian, especially where female skaters are concerned.

“Raising the age really seems like a good idea because it appears the way the sport is headed could possibly be discouraging to participation by a lot of skaters, particularly ladies, if they have to compete against young girls who have such an advantage (for jumping) with their smaller height and weight,” Zakrajsek said.

Such a change in age minimum would need approval by the biennial congress of the International Skating Union, which meets in early June. Italy’s Fabio Bianchetti, chair of the ISU single and pair committee, noted there is no proposal on the matter in the congress agenda published Monday, but Bianchetti added that any national federation can seek to file an urgent proposal up to three weeks before the congress.

The rule in place since the 2014-15 season says to compete in a senior international event, a skater must be at least 15 before the July 1st preceding the event. For several years prior to that, the age minimum of 15 applied to the Olympics and senior worlds but not the Grand Prix series and other senior events.

“I am personally in favor of increasing the minimum age to 16 (or) 17,” Bianchetti wrote in an email. “But for the time being, this is only my personal opinion and not that of the committee - not because the committee is against (it), but because we have just started to discuss the matter during the meeting held in Milan after the junior worlds, and no official decision was taken.”

Mishin, who coached the redoubtable Evgeny Plushenko to his first of five senior world medals at age 15, favors the change for competitive rather than health reasons. “It should be girls / boys and ladies / men,” he wrote in an email. “The situation looks more honest for competing.”

Viktor Petrenko of Ukraine, 1988 Olympic bronze medalist at 18 and Olympic champion four years later, thinks raising the age to 18 would “bring in more mature skating and (allow) the younger generation to stay more healthy while they are growing.”

Some attribute part of the diminished public interest in figure skating in much of the world to discontent over having senior medalists with remarkable jumps but unrefined performances that reflect being too young to have gained any artistic or interpretive understanding - even if many older skaters also are lacking in those areas.

U.S. Figure Skating President Samuel Auxier thinks a higher minimum age would help with both competitive equity and the sport's generally waning popularity.

"I think they should at least go to 16," Auxier said. "There's a right age for juniors and a right age for seniors. It would certainly be more competitive and appeal to a broader audience if they go to 17 or 18."

Discussions about minimum age have been ongoing in figure skating since the ISU instituted one of 14 (with some exceptions) in the early 1980s, beginning as a reaction to a potential trend toward what were called “one and one-half” couples in pairs: a very young, small girl partnered with an older, bigger, stronger man, allowing them to execute pairs elements more easily. It was raised to 15 for worlds and Olympics beginning with the 1996-97 season, with some exceptions that ended by 2000.

Tara Lipinski, then 15, celebrating the free skate that won her the 1998 Olympics.

Age became a hot-button issue when the three Olympics from 1994 through 2002 produced the youngest women’s singles champion ever, 15-year-old Tara Lipinski of the United States (1998); the second youngest (at the time she won), 16-year-old Oksana Baiul of Ukraine (1994); and the fourth youngest (when she won), 16-year-old Sarah Hughes of the United States.

It is being debated again with both the quad revolution in men’s skating and the triumph of 15-year-old Russian Alina Zagitova at the 2018 Olympics, making her the second youngest women’s champion.

Reacting to this story after a slightly abridged version was posted on icenetwork, Hughes questioned the merits of raising the age limit.

“Skaters develop at their own pace - some earlier, some later,” Hughes wrote on Twitter. “Should skaters who develop earlier be penalized by not being allowed to compete at the highest level?

“We also have to remember how expensive it is to skate and the sacrifice the skater - and entire family - makes for one to compete and stay involved in the sport. It’s a cost (time and money) that can’t always be maintained for an extended amount of time.”

In the past 50 years, there have been just seven women’s singles medalists under 18. Five were in the 1994-2002 period, after the end of compulsory figures dramatically reduced the opportunity for judges to mark with a “wait-your-turn” philosophy. The other two were in the two most recent Olympics, after the IJS scoring system had progressively given more emphasis and points to the value of jumping prowess (an impact that has been even greater for men doing quads.)

Zagitova is seen as just the leading edge of a wave of young Russian tyros like 13-year-old Alexandra Trusova, who landed two quadruple jumps (and seven triples) in the free skate as she won the World Junior Championships in March.

“This young girl (Trusova) doing quads now: how is she going to be when she’s 17 or 18?’’ Orser said. “It’s all fun, with everybody marveling on social media about her, but it could be a very short-lived phenomenon.”

In the four years since 17-year-old Adelina Sotnikova became the first Russian woman to win the Olympic singles title, her country has produced, briefly celebrated and immediately replaced an entire generation of female skaters.

"It's a conveyor belt, no question, and a conveyor belt of considerable talent," 1980 Olympic singles champion Robin Cousins of Great Britain told me during the Olympics. "And it's not going to stop any time soon.

"What bothers me is, where are the girls who were on those podiums four, five, six years ago?" Cousins added. "Is the goal winning medals or trying to build an athlete that can have some longevity in a career?"

Both Sotnikova and Yulia Lipnitskaia, the 15-year-old phenom and darling of the 2014 Olympics, left the sport because of injury or burnout before the 2018 Olympic season.

Compatriot Anna Pogorilaya, who won a world bronze medal at age 17 in 2016, was sidelined by back problems last season. Elena Radionova, world bronze medalist at 15 in 2015, and Elizaveta Tuktamysheva, world champion at 18 in 2015, no longer could keep up with the jumping pyrotechnics of Zagitova and Olympic silver medalist Evgenia Medvedeva, who won her first of two world titles at age 16 in 2016.

During the Olympics, Medvedeva, now 18, wryly noted how hard it already is for her to keep up with the likes of Zagitova and the younger skaters in the Moscow training group directed by coach Eteri Tutberidze.

"You feel so strange, because you are older, and you must be stronger than them," Medvedeva said.

One such girl, 14-year-old Anna Shcherbakova, is seen doing a clean quad lutz-triple toe-triple loop combination at practice in video posted on social media last week. (Coincidentally, a smiling Zagitova skates unto the picture at the end of the clip.)

Because these young Russians are utterly dominating women’s skating, Russia is likely to see any effort to raise the age minimum as punishment for their success. Russian figure skating has found a seemingly pitiless winning formula that other countries might be inclined to follow if they had the control and government financial support Russia has given to the sport since 2007, when Sochi was selected 2014 Winter Olympic host.

When Arutunian raised the age issue in Russian-language interviews four years ago, he said the reaction was uniformly “awful and negative.” Now he hears even people in Russia willing to talk about it.

Alexander Lakernik of Russia, the ISU vice-president for figure skating, said in an email, “I think that this idea needs serious research.”

Arutunian, a native of Tbilisi, Georgia who has coached in the United States since 2000, was schooled as a coach in the authoritarian Soviet sports system, which ended with the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991 but has been revived to a degree in recent years. He does not see the current Russian approach as something to be emulated.

“Why follow Russia? We should follow reality, and the reality is you want to have these kids be able to compete for many years,” Arutunian said.

“In young bodies, bones are not formed. If you do so many quads, they get damaged, and they will wind up in a wheelchair. If we don’t have evidence of that yet today, we will have it tomorrow.”

Nathan Chen does one of his history-making five clean quads in 2018 Olympic free skate.

It may seem odd to hear Arutunian speak of higher age minimums, given that he has coached a virtual child prodigy, 2018 world champion Nathan Chen, to one landmark quadruple jump achievement after another.

Chen was just 15 when he got full base value on two quads in the free skate at junior worlds; 16 when he became the first U.S. man to land four clean quads; 17 when he became first in the world to land five cleanly; and 18 when he became, this season, the first in the world to land five cleanly (and get full rotational credit for a sixth) at both the Olympics and World Championships.

“I was trying to stop him,” Arutunian said. “Because of his cultural approach, I couldn’t. When he was younger, he always wanted to do more.”

Arutunian said training Chen to do quads was not based on repeating quads over and over in practice but in doing triples with a technique that would easily allow him later to make them quads.

“When I set up the technique for an element, it does not mean I want to see them in competition,” Arutunian said. “Now, it’s not a problem. When he was 15 or 16 and starting to do quads, I wanted him to try only one. I was trying to make him do much less. Now he is 18, and it is no problem”

The sport’s current scoring and judging paradigm has encouraged skaters to try the most difficult jumps. It generally is easiest to do that when their weight/size-to-strength ratio is ideal, which, in the case of nearly all girls, is before their bodies have undergone the physical changes following puberty. There always is fear that trying to maintain that ideal ratio leads to eating disorders that primarily affect young women.

In the case of men, strength gains that usually come from full physical development in the late teens offset some of the earlier advantage that came from having a boy’s willowy body.

Two-time Olympic champion Yuzuru Hanyu of Japan did his first four-clean-quad free skate at age 22.

Canada's Kurt Browning, the four-time world champion who is credited with having landed the first quad in competition (1988), said he began learning the triple axel and a quad at age 19-20.

And Mirai Nagasu of the U.S. showed you can teach a relatively old skater new tricks: she began trying to master a triple axel at 21 and this year, at 24, became the first U.S. woman (and just the third in the world) to land a triple axel at the Olympics.

Sasha Cohen is another with mixed feelings about higher age minimums.

Cohen was 15 when she first made the podium at the U.S. Championships, 17 when she competed in her first Olympics and 21 when she won an Olympic silver medal. She took three years off from competition after that and then, at 25, returned for a shot at the 2010 U.S. Olympic team, finishing fourth in the U.S. Championships, the lone competition of her comeback.

Only the top two made the 2010 team: Rachael Flatt, then 17, and Nagasu, then 16.

Carol Heiss made the cover of SI at age 15.

.

In a text message reply to the question of raising the age minimum, Cohen wrote: “It has its pros and cons. Every body - matures at different times. But I think the sport has changed a lot. It’s arguable whether it’s for the better. It’s more like gymnastics now.”

Carol Heiss Jenkins, who has been a skating coach for 40 years, was 13 when she became the first female skater to land a double axel, 16 when she won an Olympic silver medal in 1956 and 20 when she became champion in 1960. She is against raising the age limit for several reasons, one that may apply more to the United States.

“There aren’t that many of those special young girls, and if you say they can’t compete until they are 18, you may miss out on some really beautiful skaters,” Heiss Jenkins said. “You’ll have some very talented young skaters say they might not stay in the sport if they can’t make a senior world team until 18.

“Some won’t be able to afford financially to wait until 18. And here in the U.S., kids want to go on to college.”

Zakrajsek, who taught Nagasu the triple axel, is another person of two minds about age limits, even if he endorses the idea in general terms. He does not want to deprive people of the chance to see the extraordinary.

After all, no one complained when Michelle Kwan of the U.S. began dazzling the world in winning the 1996 World Championships at age 15 – partly because she went on to a long and even more dazzling career over the next nine seasons.

“Some of the young skaters we’re watching are like the Mozart of figure skating,” Zakrajsek said. “Every part of life has its Mozart, the young prodigy beyond their years. How many Mozarts were in music?

“There is a little bit of people looking at the ones who have exceptional ability with a little bit of disdain, which bothers me. Medvedeva and Zagitova and these younger Russians – that talent and ability should be celebrated. The really good thing about figure skating is you can look at them and say, `I think Kaetlyn Osmond has a more mature look’ and then fight about which you like better.” Osmond won the 2018 Olympic bronze medal at 22.

Rafael Arutunian and Ashley Wagner at 2017 Skate Canada.

Yet Zakrajsek agrees that the sport is favoring younger over older bodies. “We’re talking about two different types of competition based on age,” he said. He would like to have a masters-type competitive circuit for older skaters, like the events that used to exist when there was a dichotomy between professional and “Olympic-eligible” skaters. But the sport’s popularity decline in North America means few U.S. promoters likely would gamble on such events.

A potential problem with raising the age to 18 would be confusing viewers who might wonder why junior skaters are doing most (or all) all of the eye-catching jumps. Just three days before he died in 1997, Carlo Fassi - who coached Peggy Fleming (1968), Dorothy Hamill (1976), John Curry (1976) and Cousins (1980) to Olympic gold - told me that age limits alone would lead in five years to having "juniors doing more difficult programs than seniors."

“So the junior champion will be doing stuff that is more technically advanced. So what?” Arutunian says. “If you don’t like it (seniors doing easier programs), go and watch junior skating.

“You have a choice: go to watch jumping or go to watch ladies skate. It’s not fair to a lady that the small kid with a boy’s body competes against her.”

Ashley Wagner, whom Arutunian coached to a world silver medal in 2016 at age 24, is a good example. Wagner’s most appealing skating came in her 20s, when she also improved her technical arsenal with a triple flip-triple toe loop combination, but her jumps were too inconsistent to keep up with the young pogo sticks the past two seasons.

Neither could another skater appreciated for her artistry, 31-year-old Carolina Kostner, despite component scores generous enough to keep her within range of global podiums.

In an unexpected way, reigning U.S. champion Bradie Tennell helps make Arutunian’s case.

Tennell was totally off anyone’s radar until last November because injuries her coach, Denise Myers, said came from lack of core strength had limited her training the previous two seasons. Tennell did intense physical training and Pilates, and she came into her own at age 19, with jumps that compared favorably to the best in the world. She would up as the leading U.S. woman at worlds (sixth) and the Olympics (ninth.)

“We don’t know if raising the age will stop the young ones from working on quads, but we all want the young men and women to be healthy,” Myers said. “How many are going to need hip replacements at age 18?

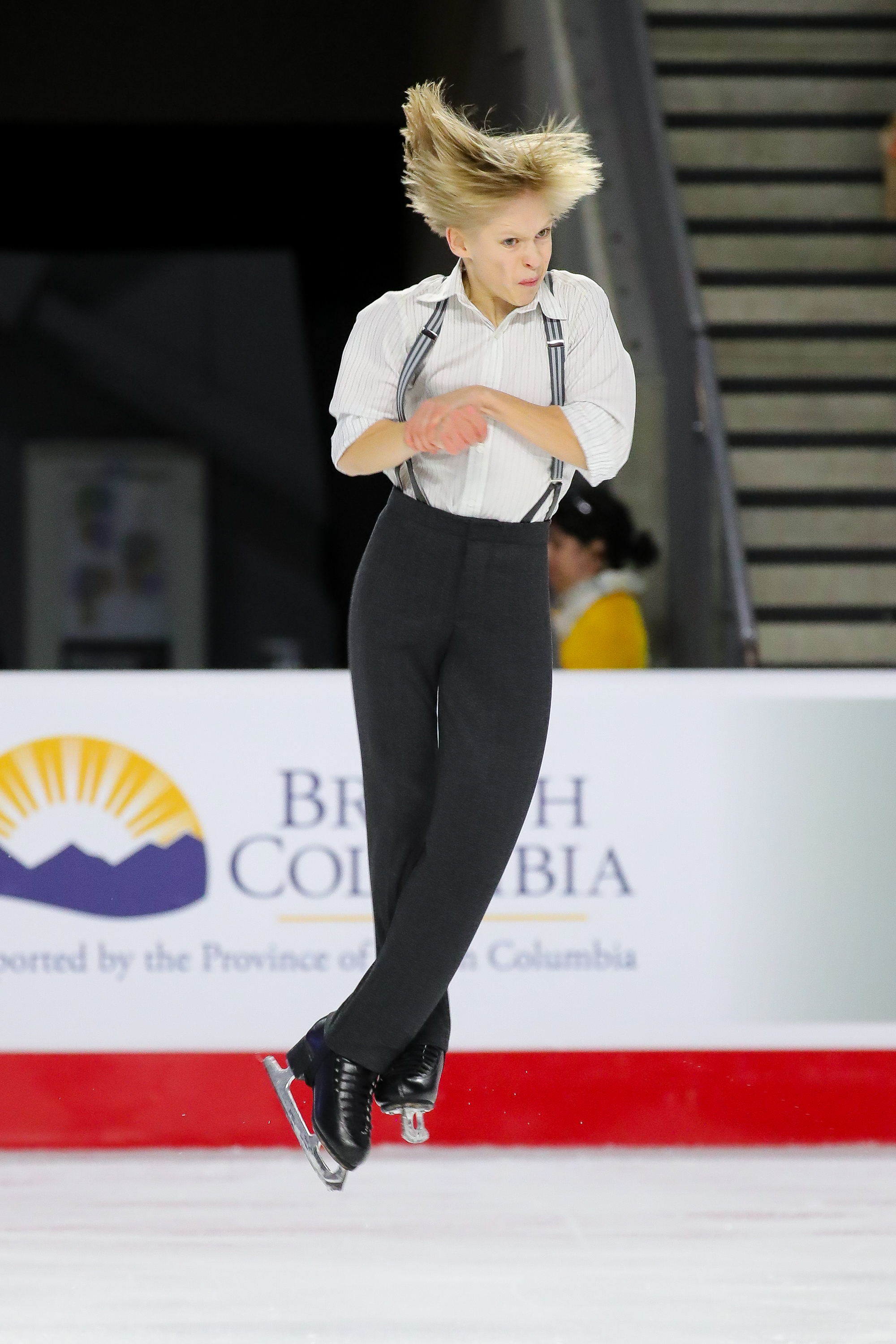

Canadian quad prodigy Stephen Gogolev, 13, competed as a senior at nationals this season. (Skate Canada / Greg Kolz)

“The days are gone where we need to rush because skating was over for so many kids when they graduated from high school. They can continue to improve if they take care of themselves.”

Orser has a 13-year-old jumping prodigy in Stephen Gogolev, who competed as a senior in this season’s Canadian championships, finishing 10th. He did a flawless quad-triple in the short program and had two planned quads in the free skate (a quad lutz, which he has been attempting since age 12, was doubled; a quad salchow other flawed but rotated).

Orser said he exercises extra caution with Gogolev.

“We are very much aware of his body and, literally his growing pains,” Orser said. “As soon as he feels any pain, we stop him from jumping until he’s feeling better, sometimes for two or three weeks, and he is happy with that. He’s not just banging them out all the time.”

I asked Arutunian if changing the parameters by putting a limit on jumps, an action Fassi favored, would achieve the same result – fairer competition, less health risk - as raising the age limit. He dismissed that idea with a smile.

“I don’t believe in saying, `You can only do this or that,’’’ Arutunian said. “It’s communism.”

(This article originally appeared on icenetwork.)