Chen's autobiography provides a rare revelatory look at the man who won Olympic skating gold a year ago

/In childrens’ book and autobiography, Chen details his oft bumpy road to the Olympic title

The idea of covering figure skating is something of a contradiction in terms.

Oxymoronic, if you will, like covering all individual sports, in which athletes compete infrequently, train all over the world, and the media rarely sees them at practice except at competitions.

It is a far cry from my experiences covering pro football, baseball and hockey, when I saw the athletes nearly every day. That is what most journalists think it means to cover a sport.

I wrote about Nathan Chen’s figure skating career for seven years, beginning with the 2016 U.S. Championships, which would be one of his many history-making performances.

I saw him only at competitions, when the chances to have insightful conversations are minimal.

Even though Chen was gracious enough to do several one-on-one telephone interviews with me, they were generally brief – although he always spoke so fast you could get 20-minutes-worth of answers in a 15-minute call. Even then his reticence to share things only he, his family and his coaching team were familiar with, matters both personal and skating-related, was very obvious.

So I never had any misconceptions about really knowing Chen or his family or what he (and they) went through in the nearly 20 years between his putting on skates for the first time and his winning the men’s singles gold medal at the Olympics exactly one year ago.

Sure, there snippets of “revelations,” one coming soon after Chen’s Olympic triumph when his coach, Rafael Arutunian, mentioned giving Chen back money his mother had paid for lessons because he knew how pressed they were for funds. And, in doing a story about his years taking ballet, I learned from his teachers what a quick study and gifted dancer he was.

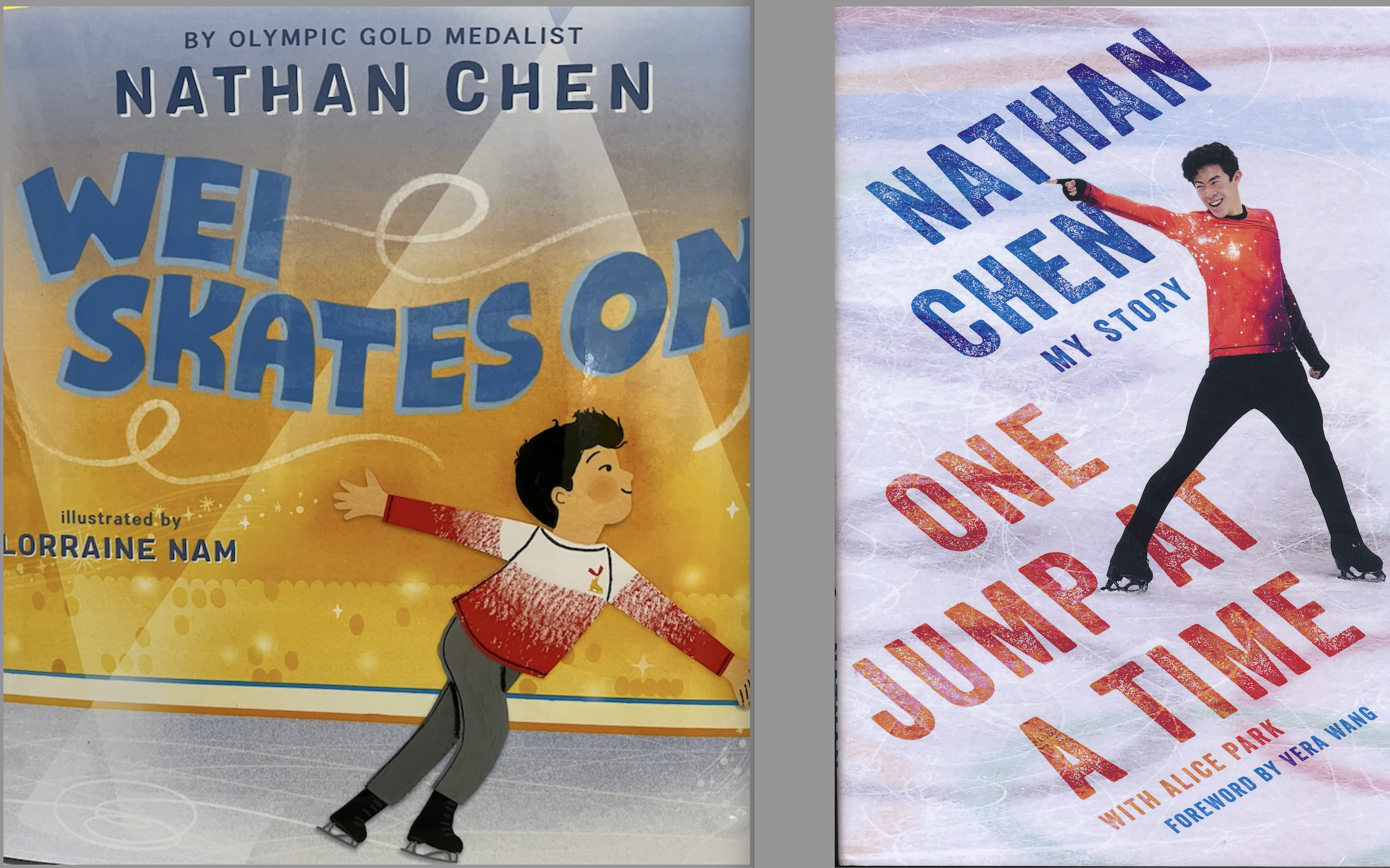

But how little I or anyone outside the shy Chen’s inner circle knew about him became apparent in reading his recently published autobiography, “One Jump at a Time,” written with Time magazine’s Alice Park.

“My family and I are naturally quiet, and we have never been very public — one thing my parents instilled in us was always to focus on the matter at hand, without distractions,” Chen told me in a text message Thursday. “My career was always about simply pursuing my dreams and goals.”

Chen, 23, opens up in the book, writing of fears and doubts and frustrations that never were publicly evident; about the near-constant injuries (one came a month before the 2022 Olympics) he never talked about lest they be seen as excuses, even though it now seems remarkable his body held up through the Olympics; about the enormous role his mother, Hetty Wang, played in his success; about the logistical, emotional and financial sacrifices his family made to facilitate his skating.

I asked via text if he ever worried the injuries might completely derail him.

“I definitely had my fair share of injures but many athletes deal with aches and pains,” he answered. “2016 (when he needed hip surgery) was the worst I had with an injury, and (I) was most worried about getting derailed from that. Otherwise, I had a great team of people around me keeping healthy enough to perform.”

He dedicates the book to his parents, his two brothers and two sisters. “Couldn’t have done it without your unconditional love, support, sacrifice and guidance,” he writes, describing in many of the 223 pages just how much his family contributed in all those areas.

The book’s sole focus is its author, leaving a reader to wish he had given some insight, perhaps anecdotal (not in any tell-all sense) about his relationship with and assessment of his great competitive rival, two-time Olympic champion Yuzuru Hanyu of Japan.

“One Jump at a Time” has a largely linear structure that can feel repetitious, but in this case it serves a useful purpose: providing private context and background in a chronological way to the relatively few moments Chen spent in front of a large public throughout his seven seasons at or near the top of the skating world.

One chapter, titled “Dread,” takes him through the difficult months that led to two poor performances in his three skates at the 2018 Winter Games, where he found himself too burdened by expectations and – as some of us later learned – listening to too many voices about the elements in his short programs.

“I just wanted to bury myself in the ice and disappear,” he writes of his mindset after botching all three jumping passes in the team event short program, a mess Chen unfortunately reprised in the individual event short program, finishing 17th, his medal hopes gone.

Rallying to win the free skate and finish a respectable fifth overall was, as I wrote then, likely to become the “most significant performance in his entire career.”

A month later, Chen won his first of three World Championship titles and set out to on what would be a convoluted path to the 2022 Beijing Winter Games - one that would include his first two years at Yale, the Covid pandemic, winning the final three of his six straight U.S. titles and, critically, recognizing the need to add a mental coach to his team.

“For the longest time, I thought that (the level of his performances) had everything to do with how well I was physically prepared,” he writes. “That ultimately proved to be my downfall in 2018. I was wrong to expect navigating something as monumental and emotionally charged as the Olympics was a solo gig.”

Nathan Chen hangs his Olympic gold medal around his mother’s neck during an appearance on the Today show.

A pause in the chronological telling of the story, at the start of the chapter that deals with overcoming mental hurdles, is the most fascinating passage in the book. He writes with forthrightness of his complicated and evolving relationship and occasional frictions with his single-minded mother, who “was such an integral part of my skating training.” Chen dedicated his gold medal to her.

“Training isn’t easy, and training with your mom certainly isn’t, and it took both of us a while to learn each of our limits.”

The sport itself is much more than it seems on the (slippery) surface, as fashion designer Vera Wang, a former skater who created many of Chen’s costumes, notes in her foreword to the book:

“The enormous toll it takes on both mind and body is incalculable, and the training and discipline it requires so imperceptible, that what often appears effortless actually defies physics,” Wang writes. “This is not a pastime for the faint of heart.”

It is an extreme sport, especially if you are Nathan Chen, who seemed to launch himself into low-level space orbit with his quadruple jumps and who, despite lingering effects of a groin injury, was fearless enough to attack the 2022 Olympics with what were the most demanding and difficult programs ever attempted in competition.

He gained the confidence to undertake such a challenge in Beijing partly by adopting a mantra about having fun rather than dread at the Olympics – and knowing that he had gained the psychological tools to deal with any fears or minor setbacks or imprecision during the programs.

This new attitude also comes through clearly in the delightful children’s book Chen has written, ”Wei Skates On,” which will be released Feb. 21. The young boy in the book frees himself of the need to define skating by winning and comes to enjoy the sport for its movement and music and the test of thinking his way through a program. Wei is Nathan’s Chinese name, and this book too is his story.

It would have been easy for Chen to downplay his desire to win, to fall back on clichés about the important thing being the journey, not the result,. His journey began while watching the 2002 Winter Olympics in his hometown of Salt Lake City, and “from the start, I associated skating and being an athlete, with the Games.”

There never was any doubt his goal was to become Olympic champion, no matter how much Chen tempered it publicly in his second Olympic season by insisting he just wanted a better experience than in 2018.

He writes about how the Olympic gold medal was heavier than he expected it to be. And he was ready to bear the weight that came with trying to win the prize he always longed for. As he says in the book’s penultimate paragraph, “It was finally mine.”

Chen, now a junior at Yale, told me he had not planned anything to mark today’s one-year anniversary. “But the month of February is always special to me,” he said.